Week Four

Day One

Pool time, then open ocean.

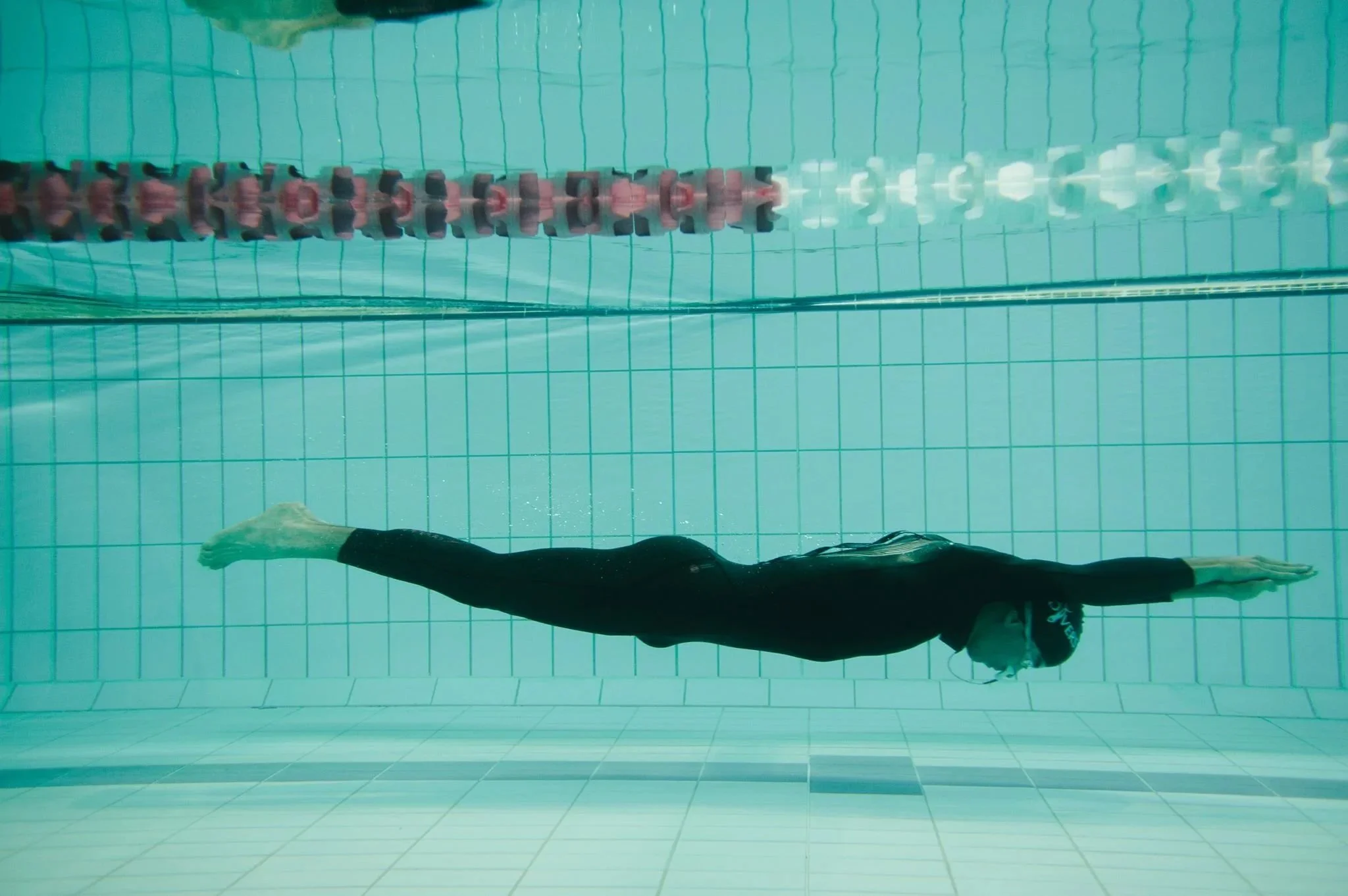

I’m learning Dynamic No Fins (DNF)—and at first, it felt less like swimming and more like a karate lesson underwater.

You push off the wall, arms extended overhead, hands clasped into an arrow. You glide. When the glide slows, your arms lower outward in a fading motion until they reach shoulder level. Elbows bend. Hands drop slightly below the forearms. Then, in one coordinated sweep, you stroke your entire arms downward and backward, pushing water behind you to create propulsion. Your hands finish along the sides of your body, palms facing down, as if you were lying flat on your back—except you’re horizontal and underwater.

As the glide fades again, you bring your arms back toward your chest, raise them overhead, hands stacked, shoulders brushing your ears—arrow position again. At the same time, you hinge at the waist, bend your knees like a squat, open your legs outward, and then discharge a powerful, circular frog kick. You squeeze the water between your legs as you stand tall again, creating forward propulsion. Count to four. Repeat.

In theory, it’s elegant.

In practice, I couldn’t even get off the wall.

I couldn’t sink. I couldn’t coordinate. I couldn’t isolate a single movement, let alone string them together. I went back and forth in the 25-meter pool, breaking the sequence into pieces. Try after try after try.

Finally—around the seventh attempt—I felt it. A small glide. A hint of propulsion. The lesson wasn’t technical. It was internal: slow down and relax.

At 63, you quietly question how much you’re still capable of learning. That question showed up—but it didn’t stay long.

Day Two

I walked into the pool confident.

Surprisingly confident.

The night before, I had downloaded a video of a woman completing 100 meters in eight strokes. I isolated her full sequence and practiced it on the bed—over and over—until it finally made sense in my body. I committed to knowing the movement, not just understanding it.

Back in the pool, I pushed off the wall.

One stroke.

Then another.

I was moving. I could feel the energy generated by my own actions. The first attempt got me halfway. The second nearly reached the end. On the third, I got cocky. I started expecting progress every time.

That’s when I stopped myself.

Learning isn’t linear.

I gave myself grace. Real grace. I reminded myself that I’m choosing to learn something complex, technical, and rarely attempted—especially at this age. DNF is one of the hardest disciplines in freediving because of how perfectly the movements must synchronize to conserve energy and maximize glide.

Repetition would come. Progress would follow.

Day Three

I couldn’t reach 20 meters.

That surprised me.

I had already been there easily before. This time, I stalled around 15. Equalization failed. Every attempt stopped short. I realized I had become casual—expectant. Cocky.

The deeper truth emerged quickly.

On previous dives, I had been descending slowly using free immersion, unknowingly allowing CO₂ buildup to trigger subtle convulsions. Those convulsions forced my glottis open, unintentionally pulling air into my mouth from my lungs. I didn’t realize it—but that’s how I’d been refilling compressed air to equalize.

This time, without that accidental assistance, I ran out of usable air in my mouth. As depth increased, the air compressed to a fraction of its volume—no longer enough to equalize.

The solution was clear:

Learn Frenzel properly. All variations. Sequentially.

That meant learning to isolate and control muscles I’d never consciously used—larynx movement, tongue positioning, throat compression. Muscles that normally operate automatically now required precision awareness.

So there I was, on a rare day off, practicing throat mechanics:

Moving the larynx up and down

Moving it with my tongue extended

Separating muscle groups one by one

It felt absurd. Necessary. Non-negotiable.

If you want to go deeper, you must earn it.

Day Four

It finally came together.

In the pool, the movements clicked. Now that I could propel myself, I had to learn control—steering, head position, alignment, awareness of trajectory so each stroke corrected the next.

So much to integrate—but now I had direction.

Back in the open ocean, I descended past 20 meters with intention. This time, I knew what had been happening before. I was no longer relying on accidental air intake. I was deliberately managing air, timing, and equalization.

I also began to clearly feel the phases of the dive:

Positive buoyancy at the surface—where you must actively pull yourself down

Neutral buoyancy—a calm, balanced middle zone

Negative buoyancy—where gravity takes over and you drop effortlessly

About ten meters per phase. Distinct. Learnable. Repeatable.

Much of it blurs together now—the repetition, the drills, the quiet hours in the pool and ocean. Most people only ever see the results. They don’t see the work beneath the surface.

I’ve surrendered to Dimas’s schedule and work ethic. It’s demanding—beyond my comfort—but necessary. I’m here for two months to progress, and that means stepping fully into his world.

I don’t complain.

I comply.

He sets the time. I show up—enthusiastically. I support the process because in the end, I’m the one benefiting.

I’m now diving consistently past 20 meters without issue.

Nothing more to say.

Repetition.

Repetition.

Repetition.